Truth-makers, truth-bearers, truth-breakers

Truth and identity

July 11, 2020

Negative truths

August 11, 2020Intuitively, a world where a proposition is true differs from a world where it is false. But how to express the relation between ‘truth-bearers’, e.g. propositions, and their ‘truth-makers’, the aspects of reality they refer to? The idea to single out truth-makers for specific truth-bearers and express them in one to one truth-making relations has shown to be a dead end. Relations between propositions and reality are plural.

Besides truth-bearers being true in virtue of truth-makers, the nature of the relation has been expressed as entailment, necessitation, relevance, projection, essence, and grounding. All of these seek to find a middle-of-the-road between atomic, one-one correspondence, and total reality making true the coherent whole of our knowledge. (For further discussion and explanation of the above, click here.) In spite of refinements, all of these relations are one-directional, singular forms of entailment: “If state of affairs s, then proposition p.”

Asymmetry

If we believe something to be true, it still needs to be expressed in language to become shareable knowledge. Again intuitively, the truth relation between language and existence is asymmetrical. States of affairs may give reason to propositions, but not the other way around. David Armstrong wrote that trying to express the relation as entailment leads to a “category mistake”: logical relations can only exist between propositions, so not between material reality and its expression in propositional language.

To give truth-maker theory a chance, my attempt to express it would be: “Truth-makers exemplify the truth of truth-bearers.” Exemplification is semantical and bidirectional. Every time we see snow falling, it is an example of the truth of the propositions that “Snow is white”, that “Physical objects are subject to gravity”, that “Snow consists of water crystals”, etc. So, one ‘simple’ phenomenon may exemplify various truths. In the opposite direction, we ourselves grab together the truth-makers for the proposition that “Physical objects are subject to gravity.” It is exemplified by objects rolling down slopes, waterfalls, whirling snow. Human knowledge was originally shaped by induction from events that somehow resemble each other. We have an inclination to notice patterns and to act on them even if our knowledge is incomplete, by both systemic and heuristic thinking. This is typical for humans and many other animals, and most probably an asset in the struggle for life, see Knowledge and reality. Therefore, the relation between truth-makers and truth-bearers is plural in both directions. It can be analyzed by plural exemplification.

Once again intuitively, unique aspects of phenomena exemplify nothing: what counts is the resemblance between them. Armstrong tried to define a general, or totality fact as a relation between an aggregate on the one hand and a property on the other, that exists when the aggregate comprises all the items that fall under the property in question. This would make “Physical objects are subject to gravity” a paragon of a totality fact, while in “Snow is white”, snow would have to share its whiteness with the totality of all other white objects. In my opinion, this is just class nominalism under a new flag. What makes white objects white is their reflection of almost the entire light spectrum visible to humans, a physical capacity we humans call ‘white’, and not by white things being a class given by reality itself. A relevant connection between truth-makers and truth-bearers emerges in a natural way as a result of the interaction between physical phenomena, and these include human sense perception and human thinking.

One of the key philosophical misfortunes of humanity is our failure to accept that everything there is to humans is ultimately physical.

Examples, by definition, are neither one-one truths nor the expressions of a totality. Exemplification counts out accidental truths such as the Gettier cases. Since examples tend to express generality, they only provide truth-making for what we consider to be general truths. But truths do not exist mind-independently: they are interpretations, however true they may be. The real issue is to define exemplification itself.

Events and states of affairs

But first we need to decide if we are going to distinguish between events and states of affairs. I rather avoid a strict distinction between events and states of affairs. ’State of affairs’ implies absence of change for some time, while ‘event’ refers to something with a limited time span. In ordinary language, day and night are states of affairs, while sunrise and sunset sound more like events. All of them are caused by Earth turning around its axis, where every single turn may be called an event – because of its definable beginning and ending –, while the ongoing turning itself is rather described as a state of affairs.

Obviously, the definitions of event and state of affairs are arbitrary.

A living thing being alive is a state of affairs, while its birth and death are events, even if we say that something ‘is dying’. Just like living things, also objects come into existence and perish. They undergo changes, however little: they change places, colors, wear away, evaporate, undergo chemical reactions, and relate to different other objects and living things. So, the difference between state of affairs and events can only be gradual, and their definitions are nominal. Both are better called processes.

The basic ontological features of the universe are processes, so not static substances and their properties. The latter view has been the mainstream in Western philosophy ever since Aristotle. This substances-properties paradigm roots in outdated knowledge, that is, in physics from before the scientific revolution of the 17th century. Nonetheless, already in the 6th century BCE Heraclitus of Ephesus – renowned for his panta rhei – everything flows –, described the world as a dynamic balance between opposing forces, proceeding in a flow of patterns or natural laws. Shifting the emphasis from being to becoming, process metaphysics corresponds better with common sense and with a naturalist view of the world, as well as with modern science.

Processes are multicausal and non-teleological interactions; they move nowhere special. They are clusters of phenomena interpreted as change over time. To interpret changes, we need distinct begin- and endpoints, but of many processes these are not ‘given’, and the speed of processes only exists in relation to others. Processes are interactive. Since time is relative, the temporal aspects of processes must be related to other processes and we are inclined to map newly discovered processes on already existing knowledge of other processes. Since processes are interwoven by complex multicausal relations, it is difficult to describe them without some degree of ceteris paribus. And finally, processes are ‘run’ by existents with unique identities. These identities are enormously fine-grained and knowledge of them is always incomplete, see Truth and identity. So, processes can never be described completely; all descriptions of processes are generalizing models.We ourselves define the spatiotemporal covering of a process, its actors, its mechanisms etc. To find truth-makers, we first have to do some work on reality, to select and put together aspects from its content.

Finding truth is self-service dining from the menu of reality.

Exemplification

Exemplification is not an instantiation of universals, but recognition of resemblance. Resemblance is seen in repetition of similar patterns, either physical, biological, social or moral. Let us consider: “Liquids conform to the shape of their containers, but they do not disperse, like gases do.” This true proposition is exemplified by uncountably many different liquids. Now we have two options to define ‘truth-maker’: either (a) every single vat holding a liquid is a truth-maker for our proposition, or (b) the similarity between them is the truth-maker. Option (a) refers to physical reality: uncountably many cases of liquids in natural and artificial vats, but all of them of different chemicals at various temperatures with different viscosities in containers big and small.

Philosophers, however, are interested in the metaphysical structure behind all of these phenomena. To trope theorists, (a) is attractive since all liquids will have their very particular type of liquidity, a trope. They see tropes as the elementary metaphysical parts of the world. But what brings all of these tropes together? As for (b), to count as truth-maker, also this similarity will have to be something metaphysical. If the property of liquids to conform to the shape of their containers is a universal, it is instantiated by every liquid. What might that universal be? Liquidity? And if liquids are a class, all particular cases of liquids belong to that class because they are … liquid: most relations between universals and their instantiations or between classes and their members are inflated tautologies. Moreover, solutions like universals, classes or tropes require the acknowledgment of abstract objects. And the most important: truth-makers for general truths necessarily are generalizations from individual phenomena and generalizing is essentially an interpretative process.

But this is not what truth-maker theorists aim at. They speak of physical realities as ‘given’ truth-makers, creating two problems. Should they allow abstract objects also, these will, again, themselves be in need of grounding, leading to a path of regress. Worse: truth-maker theorists are chronically unable to link propositions to physical reality other than by logical or semantical notions. The reason is that many of them wish the outside world to reveal its ‘truth’ to us, an attitude with clearly recognizable religious roots.

The result is a mental picture of reality of which they nonetheless deny that it is a human construct.

Resemblance nominalism is different from its metaphysical stepsisters universalism, particularism, or tropism. It is an indirect-realist position. Similar to what I wrote about roses in Truth and identity, liquids do not resemble each other because they are liquid; we call them liquid because they resemble each other. We have systemized the physical state of materials into solids, liquids, gases, and plasmas. Liquids show similar, but by far not identical behavior. If we say that under certain physical conditions a material exemplifies liquidity, it does not show a ‘given’ state of affairs, but one defined by us humans. Things do not show themselves: perception is the physical interaction between the outside world and our perception in which our senses and brain work together in one system: there is no independency between mind and senses.

Consistency, entailment and disjunction

A fourth intuition tells us that reality is consistent, so, if we see the whole of reality as truth-maker for the whole of knowledge, then all true propositions are necessarily consistent. Consistency is stronger than coherence. While the latter refers to an intelligible whole, the former expresses the compatibility of its parts, famously shaped into the principle of non-contradiction by Aristotle: p and – p cannot both be true. This logic principle bears heavily on necessary truths, those truths that are independent of time and space, such as “Physical objects are subject to gravity” or “Snow is white” – so not: “The roses in my garden are red”, since I might have planted yellow roses should I have preferred to do so. The so-called disjunction thesis says that if a truth-maker s1 (for state of affairs) entails that proposition p1 is true, this implies that there can exist no sx that makes – p true. Since reality is consistent, s1 not only entails p1, but also p2 … pn, so gravity affecting all objects also entails that “Snow is white”. The opposite is also the case: p1 (and in fact px, any proposition) is made true not only by s1 but also by s2 … sn. We end up with the set of all states of affairs {s1, s2, …} making true the set of all propositions {p1, p2, …}, but we cannot create pairs where s1 entails p1, s2 entails p2, etc. The disjunction thesis conflates the consistency of reality with logical consistency. The former, the consistency of {s1, s2, …}, can hardly be doubted, but not be proven. The latter, the consistency of {p1, p2, …}, needs formal proof, but as we saw above, it cannot be logically related to reality. We chronically stumble on the threshold between truth and validity, or between reality and logic.

According to the disjunction thesis, a truth-maker s may entail p v – p, since if s entails p, by addition it may entail any disjunction, so also a disjunction with its opposite. But those holding that p v – p is always true abuse the rules of propositional logic. If we consider p V q, a simple disjunction, this means that p or q or both are true. But in p v – p they cannot both be true, one may argue: these are contradictory. Right, so effectively, the premise is p ⊻ – p, an exclusive disjunction. That, however, would be very inconvenient, since, as every student of propositional logic knows after a few weeks, s -> p may, by the rule of addition, be expanded to s -> (p V q V r) and so on, but not to s -> (p ⊻ q ⊻ r). The latter is useless to express the disjunction thesis since it singles out the relation between a truth-maker s and either of the propositions p or q or r; in many comments on the disjunction thesis the meaning of the word ‘either’ is used in an unclear way. Imagine the case where two different propositions contradict each other, “Snow is crimson” (p), and “Snow is white” (q). Obviously, white is not crimson, but that does not imply that p and – q are equivalent, since “not white” may imply “crimson” but also “any other color but white”. So, adherents of the disjunction thesis mix up the free addition of simple disjunctives with mutually exclusive propositions.

Entailment revisited

Since the truth relation is asymmetrical, we are wary of its expression as a biconditional. So, let’s make it a simple conditional. But in which direction? The essence of entailment is that a sentence implies more than it says explicitly,. “One of my cats died” implies that I have more cats and that I am not talking about my collection of cat statues. Nonetheless, philosophers use entailment for one-directional implication by reality on language, but it may just as well be the other way around. So let’s check out both.

Let’s split it up and use either (i) s entails p, or (ii) p entails s. Hypothetically, these are not material implications, but semantic entailments, where s means the belief that some state of affairs exists, and p means the belief that a proposition truly expresses this state of affairs in language. Thus, they both express beliefs and there seems to be no category problem.

But the above is highly inaccurate. With s, we have two options: it expresses either a mind-independent reality or a mind-dependent belief in such a reality. In the latter case, s becomes itself a proposition and loses its status as a state of affairs. In the former case, s is material, so, first, it can entail nothing – see Armstrong’s view above –, but only materially implicate something; second, it cannot be false; it can only not exist. Which is the better option? Since a single state of affairs may make true various propositions, it is not s as such that counts, since processes cannot be described fully. It is always something about s that exemplifies a certain proposition. This ‘about’ needs to be selected from s to enable exemplification. It cannot exist mind-independently: therefore, s cannot be material. So, we are stuck with s as just another way to formulate a proposition.

With p, we also have two options: either p expresses a proposition, stating that something is the case, or p expresses the belief in a truth. And these are not the same. If ‘truth’ lives somewhere in the neighborhood of s and p, it obviously is not captured by the proposition itself; it is where the logical operator (‘entails’) is..This means that p itself is nothing but a statement that something is the case. Going back to our definition of s, we notice that s and p are expressions of the very same belief and if these are on par, this is because they are semantically equivalent. Consequently, ‘aboutness’ or ‘relevance’ is no longer a problem. The real problem is that semantically equivalent expressions entail each other by definition.

Let us look at (i) s entails p and (ii) p entails s to see if we can escape from that circularity. Both (i) and (ii) are plausible ways to express the relation between s and p. Also, both may be transposed, to (ib) , – p entails – s and (iib), – s entails – p. In spite of both (i) and (ii) being worth consideration, many studies stick to (i) without further ado. Premise (i) means that if we believe s to be the case, this implies the belief that proposition p is true. Though obvious, (i) is epistemically trivial since a proposition p will only emerge from a belief that s is the case: to become knowledge, only propositions that claim to represent reality are to be taken seriously. The second premise, (ii), means that if p is believed to be true, this implies that s is believed to be the case. In fact, (i) and (ii) express exactly the same. Together, they look suspiciously circular.

But the picture may change if we look at their transpositions: (ib) says that if proposition p is believed to be false, then s is believed to be not the case. But proposition p will only emerge from a belief that s is the case; we do not maintain propositions that we believe to be false, so the premise is trivial. The other transposition, (iib), says that if we believe s to be false, then we believe that p is false also. But in such an unrealistic case, we would immediately reject p. This all means that neither (i) nor (ii) is very useful, and they do not get better if we make a biconditional out of them.

The more interesting cases arise from the notion that between s and p there is a difference of role: if s is to be a truth-maker, it cannot be false. Even negative truths need positive truth-makers to show that they are negatively true, see Negative truths. The truth-maker of “Snow is not crimson” is the state of affairs of snow being white. Therefore, premises containing – s do not come into consideration: neither (ib) – p -> – s nor (iib) – s -> – p will help. There is still another reason to dismiss (i) s -> p, since if s cannot be false, by modus ponens, neither can p; the premise does no serious work at all. But p is a proposition about reality; we may err, so – p is a plausible case.

We need a new premise. Only (iii) s -> – p can express truth-maker entailment: reality shows that p is false. By modus tollens, if p is true, then s will be the case.

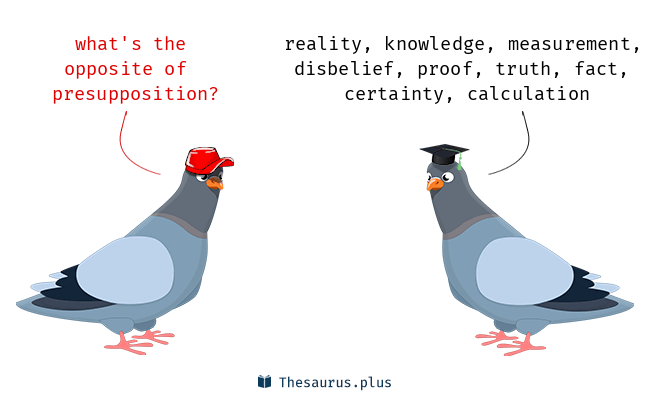

Reality is not a truth-maker: it is a truth-breaker.

This is of course far from new: Karl Popper made clear that all scientific knowledge is provisional, and that we should not rely on induction, but on falsification instead.