Coincidence, determinism and free will

Knowledge and facts

June 9, 2020

Truth and history

June 23, 2020A man leaves his office, unsuspectingly walks past a house where a roof tiler accidently drops a tile, killing the man. Fred sits quietly in his room when a sudden gust of wind slams his window shut. That evening they call to tell him that his best friend has had a fatal car accident. In the course of some party game, two people appear to have the same birthday.

Coincidences are events happening simultaneously, somehow connected, but seemingly without common cause. Unbelief in coincidence gives rise to a lot of speculation, complot theories and explanations from the supernatural, partly as forms of determinism, the view that events are causally determined by earlier states of affairs, or even that the entire universe is a determinate system. Determinism has philosophical, scientific as well as religious roots. Views opposing it traditionally emphasize human free will. I shall argue that both determinism and free will are best taken cum grano salis.

Why coincidence?

Above are three cases of coincidence. The first, originally presented by the French mathematician and theoretical physicist Henri Poincaré, is a genuine coincidence. Two events, the passing of the man and the falling of the tile happen simultaneously, causing the death of the man. The two events do not share any direct cause. Had one of them taken place slightly earlier or later, the man would not have been hit. In the second example, two events happen more or less simultaneously, but they do not share a consequence other than Fred’s thoughts.

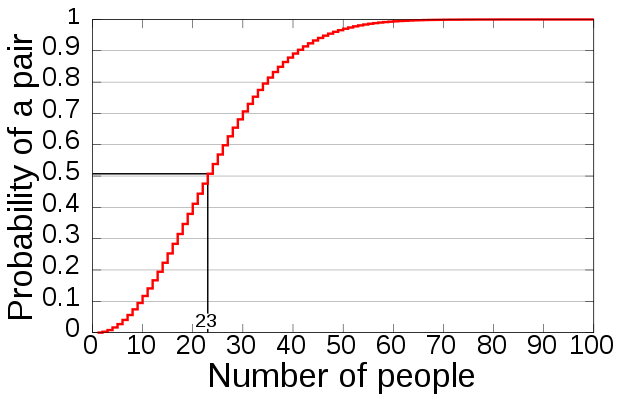

The third example is merely a statistic issue. Intuitively, most people are inclined to underestimate both probability and possibility. Already in a party of 23 people, the chance that two people have the same birthday is over 50%.

Would it be possible to survive a toss for heads or tails ten times in a row? Common sense may say no, but all we need is a knock-out tournament over ten rounds with 1024 (210) competitors. There will necessarily be a winner who achieved to survive ten rounds. The larger the tournament, the luckier the winner will have to be, but mathematically, the series is infinite. This shows that the idea of coincidence is caused by both big numbers and lack of logic.

With Fred’s case, the problem is selection. In daily life, we form beliefs by selection from direct observation, and we combine them afterward. Should Fred have got up to close the window earlier, he might have seen a black cat sitting on his lawn, rising to the status of a magical sign of bad things to happen – but only later on. If there hadn’t been a black cat, Fred might have connected the death of his best friend with any special observation from the days before he got the bad news. Fred himself connected the events, and also set the degree of tolerance for the time difference between them.

There are many different types of belief where people see causal relations where there aren’t any. This fallacy comes in many types, ranging from sports shirt fetishism or gambler’s fallacies to prayer for physical or material help. All of these are at least partly irrational. Another case is to see correlations as causalities, such as in the famous cum hoc ergo propter hoc, Latin for “with this, therefore because of this”. These are logical fallacies, of which there are many types also, both formal and informal. Their nature is more rational, for example, to say that the man in Poincaré’s example was killed because the tiler dropped a tile, or because he chose to walk on the sunny side of the street, or because he went out for lunch early. These are not causes, but correlations.

On the other hand, people often miss or ignore causal relations between the formation of new beliefs and their own mindset, such as tendencies to prejudice, partisanship or merely a tendency to wishful thinking. Most people tend to favor confirmative information, a feature known as confirmation bias. A special branch of this is systemic thinking. Most probably, this capacity to recognize patterns – such as signs of danger – was a plus during evolution. All of these are examples of heuristics, processes used by humans, animals and also machines to solve problems involving uncertainties quickly and effectively without having to know all aspects. Recent studies show that in cases where uncertainty plays a part, ignoring information is rational.

Heuristic strategies are an integral part of how the human mind works. But at the same time, we are craving to know the big secrets of the universe. So, it looks as if we are digging for diamonds with a pocketknife.

Determinism and free will

One of these big secrets is if the universe is physically determined. Determinism roughly holds that all events, including all human behavior, are determined by unchangeable causal chains. This goes together with the idea that things could not have developed otherwise and that in theory, all developments would be predictable if we only knew exactly what is governing them. This so-called causal determinism is closely related to predeterminism: if unchangeable causal chains can be followed backward, then everything happens according to some initial plan or set of conditions, often said to be conceived and incited by some godhead. This last position is less deterministic than causal determinism since it looks compatible with free will.

There are almost as many accounts of free will as there are philosophers, so let’s have one more. A common account of free will is that humans can make choices. There can be little doubt that choices are limited by physical conditions. One of the problems with defining free will is that the conditioning of our choices is both physical and mental. We might want to fly up in the air like birds, but we can’t because of physical and biological impediments. At the same time, our minds are conditioned by these impediments to such an extent that the choice between flying away and staying on the ground isn’t even actual. This is part of being the way we are, a subconscious mental state that may be the result of a determined evolutionary process. But we humans have a history of evaluating the working of the human mind and have become aware of this subconscious mental state. When we became conscious of our impediments as well as possibilities, both physical and mental, free will became the choice to either behave accordingly or not. As a result of systemic thinking, the belief that determinism is true will easily lead to fatalism.

Free will is the choice to whether or not defy determinism.

Defying determinism

But if determinism is false, the above definition of free will becomes useless. So, what is determinism? The preliminary definition given above – that all events, including all human behavior, are determined by unchangeable causal chains – is hard causal determinism. It implies the idea that everything is reducible to the physical – although some philosophers like Galen Strawson say that the physical itself is mind-governed, a remote echo of Spinoza’s pantheism. The opposite question is if we will ever be able to explain the mental from the physical. This is the major problem of physicalism, the idea that everything is essentially physical. There’s a huge epistemological caveat here. ‘The physical’ would mean a system of physical laws – or rather theories – that convincingly explains the basics of what goes on in the universe. Since physical laws are not realities, but facts in the sense of formally true propositions – see Knowledge and Facts –, again we encounter a circular argument: if ‘the physical’ needs be convincing, it becomes dependent on the mental, not the other way around.

The above shows that determinism cannot be known from experience; it is a metaphysical theory. How did people ever come to believe in it? Avoiding too much detail: universal causal determinism was propagated by the Stoic philosophers, who at the same time were proponents of ataraxia, a fatalist acceptance of come what may. In Jewish and Christian theology, fierce discussions rose over the theodicy: why does benevolent, omnipotent, predetermining God permit evil to exist? From Newton onward, the idea of direct divine influence began to be replaced by the theory that physical laws govern the universe – laws either created by God or not. Darwin’s evolution theory made it possible to expand determinism to life as well – although Daniel Dennett convincingly explained why this is wrong. According to some, in his Sapiens – A brief history of humankind, Yuval Noah Harari showed the deterministic course of human history, but Harari himself denies this, mentioning examples of highly unexpected developments – such as the success of Christianity. A psychological force behind all of this deterministic thought we already met above: systemic thinking.

We need to clear up the common conflation of determinism and predictability, also seen in Harari’s denial. Here we hit on Edward Lorenz’ deterministic chaos: “When the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.” Simply put: physical and biological systems are causally determined, but that does not imply that the results of these processes are predictable, not even in theory. We may know why they move as they do but not where. Weather reports show why this is true: meteorologists thoroughly know the physical laws that govern the weather and use ever more sophisticated computer models, but their forecasts remain uncertain because of what we call sensitivity to initial conditions, also known as the butterfly effect. As becomes clear from mathematical models of chaos, a tiny difference in the initial conditions of a physical model can lead to an enormous divergence of possible results: a butterfly spreading its wings in Brazil may cause a tornado in Texas. Already Aristotle saw this when he wrote that “the least initial deviation from the truth is multiplied later a thousandfold.” Most mathematicians and scientists agree that the majority of physical systems are nonlinear and dynamic. In these systems, change over time is not linear. It is ruled by unpredictability, counterintuitive results, or even incomprehensive chaos, which in turn influences the initial conditions of related systems, in turn tickling these, and so on.

Under the already twice-mentioned definition – all events, including all human behavior, are determined by unchangeable causal chains –, determinism is false, but we may repair it, if we take out ‘unchangeable’, the claim that we cannot change the future. We might, for instance, save life as we know it by not ruining the climate. If we succeed, determinists will say that our mental conditions leading to saving the climate were determined by unchangeable causal chains, working in our minds, the economy, politics, and so on. If we don’t succeed, they will say exactly the same about how we ruined the planet. They are no better than Fred linking up events from hindsight bias and they cannot accept that somebody sometimes drops something on somebody else’s head totally by coincidence.