God as a stopgap

On the analytic-synthetic distinction

August 21, 2020An awkward, yet a frequent argument for the existence of God is that science is unable to explain everything. In this view, God is complete knowledge minus science. As scientific knowledge grows, God is confined to a constantly shrinking, mystic leftover territory. In this article, I shall argue that the supposed contrast between science and religion is of a much different nature.

Belief in the possibility of knowledge of ‘the entire truth’ is known as dogmatism. The opposite position – true knowledge is an illusion – is skepticism. A middle position, more or less common to all contemporary philosophers, is fallibilism: we know quite a lot, but no human beliefs can have truth-guaranteeing justification. Therefore, knowledge doesn’t require absolute certainty. My articles on The metaphysics of truth and The epistemology of truth make clear why this position makes a lot of sense: truth as the universal quality of reality does not exist.

Knowledge and belief

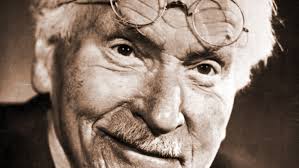

In a famous 1959 television interview the famous Swiss psychiatrist and writer Carl Jung, on being asked if he believed in God, replied: “I don’t need to believe, I know.” Jung immediately regretted what he had said, fearing it would be interpreted as blind faith. And it was, very much later still by Richard Dawkins in his book The God Delusion.

How may we distinguish between knowledge and belief? In classical epistemology – the branch of philosophy studying the nature and boundaries of knowledge – knowledge was often defined as justified true belief. In Knowledge and truth, I demonstrate why this theory is wrong. In The metaphysics of truth, I already wrote that truth is not a universal quality. The predicate ‘true’ does not refer to reality, but to propositions. There is no material truth, there are only formally true constructs of facts, see Knowledge and Facts. This restricts the difference between belief and knowledge to some degree of justification and nothing more. In 1963 however, it took Edmund Gettier only three pages to explain that sometimes people are justified to believe things that are false, tearing the notion of justified true belief to pieces. Gettier pointed out that for knowledge, justification is necessary, but not satisfactory, see again Knowledge and Truth.

This leaves us with the uncomfortable suspicion that knowledge cannot be distinguished from belief on the basis of the qualitative criteria for knowledge itself. Neither very promising is to refer to scientific methodology to distinguish knowledge from belief, since as both metaphysics and religion show, beliefs may just as well be the product of institutionalized, methodic thinking.

But unlike metaphysics, scientific knowledge roots in observations, in spite of the fact that a lot of scientific knowledge is ‘just’ theory; it claims to be logically consistent with a generally accepted set of basic observations, but in many cases, it is still waiting for further confirmation by observations or experiments. The distinction between scientific knowledge and religion, however, is far less clear. Religion may also claim to rely on observations, namely of the beauty and harmony of God’s creation. Yet, God to be the driving force of the entire universe can never be proven by direct observation.

Obviously, nothing supernatural can be known from the natural.

So, any claim to know that something supernatural exists can only be a priori, generated by innate knowledge. Scientists believe that some innate knowledge does exist, but most probably, it is rather about competencies to acquire knowledge than about factual knowledge. One of these competencies of the brain is agency detection, necessary for our survival. David Hume wrote:

‘”There is a very remarkable inclination in human nature to bestow on external objects the same emotions which it observes in itself, and to find everywhere those ideas which are most present to it.”

Or: we only have to see the whole of the cosmos as an object and to mobilize our agency detection to see the hand of God in it.

To become knowledge, the ‘God-theory’ will have to be consistent with the rest of scientific theory – see also: Why can’t we just let Him be. An important note here is that ‘consistent with’ scientific theory means more than its negative definition of ‘not contradicting to’. We are also bound by Ockham’s Razor – see also: The epistemology of truth. A theory must be necessary to explain occurrences in conjunction with other theories. Simply put, if explaining the universe works just as well without involving God, he is to be left out. This appeal to consistency is essentially the same as that of the Five Ways. Thomas Aquinas also started from the accepted scientific theories of his days, largely based on the works of Aristotle. But Aquinas was far too cautious to speak of absolute truth.

As for Carl Jung, his true position was rather that he was deeply convinced of God’s existence but knew to be unable to fully understand his own belief, let alone communicate it to others. In a letter , he wrote: “The God-image is the expression of an underlying experience of something which I cannot attain to by intellectual means.” This is very similar to a famous statement of Johann Gottlob Fichte, who wrote: “My entire conviction is only belief, and it comes from mindset, not from reason.” Like many other great minds of the past, he saw, that unlike believing that God exists, knowing that God exists is utterly naïve.

Science and belief

Few people will deny that since the days of Thomas Aquinas scientific knowledge has grown tremendously. This observation gives rise to an uncomfortable logical argument:

1 God is reality’s first cause

2 Science studies reality

3 Hence, science studies God

4 Scientific knowledge is belief plus justification

5 Hence, science is better than belief

6 Therefore, to study God, science is better than belief

So historically, scientific development should have led to more knowledge also of God. But, although the idea of centuries of conflict between religion and science is totally obsolete, who would support the view that the development of science brought us any closer to God? This might mean that there is something wrong with the first three lines of the above argument, for example, that science studies reality, but deliberately chooses to ignore God’s part therein when building its theories.

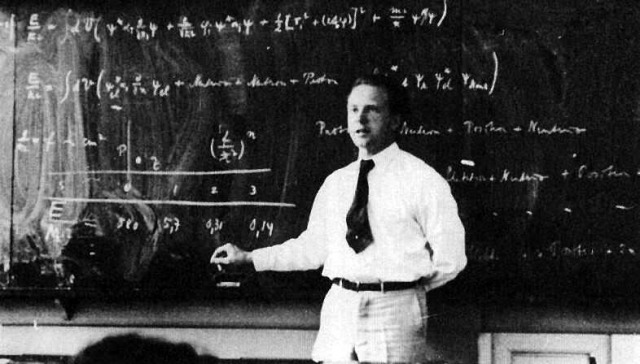

That would be a blunt undervaluation of the views of many deeply religious scientists. Werner Heisenberg, a devout Lutheran, who in 1927 introduced his famous uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics, wrote: “The first gulp from the glass of natural sciences will turn you into an atheist, but at the bottom of the glass God is waiting for you.” Many other scientists, including Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein, made similar statements. By studying what is often called God’s ‘book of nature’, their religious feelings were rather nourished than denied. And why not? In principle, rational interpretation of the “book of nature” might very well justify belief in God. In his 1998 encyclical Fides et Ratio, Pope John Paul II writes: “Although faith, a gift of God, is not based on reason, it can certainly not dispense with it.”

However, as we saw above, this justification can never come directly from sense perception, but only from a consistent theory with convincing proof of God’s presence. So far, this kind of proof has not been given, although many scientists would gladly have given it if they just could have. Their religious awe for the wonders of the universe obviously stiffened their belief, but it should not be mistaken for knowledge of God’s existence. Contrary to the big scientific theories of our days, there is no widely accepted scientific theory explaining God’s necessary role in the universe. On the contrary: God’s former miracles are being explained by science one after the other. While in the days of Thomas Aquinas God’s role as the first cause of the universe was still paradigmatic knowledge, in our days we are far less convinced. This might imply that in the above argument there indeed is a false premise, the first: God is not necessary as reality’s first cause.

On the fly, we also gave an improved definition of knowledge: knowledge is belief justified by consistency with a set of generally accepted basic observations. Belief in gods as directly influencing the affairs of the universe does not meet the above criterium. This is not another way of saying that I think there are no gods. Once more: asking if God (or gods in general) exists is a bad question. I only say that we cannot develop a theory of God that is supported by widely accepted scientific knowledge.